XIV: ESCAPE

Then the prophet Mortan said to the congregation, as they stood among the remains of the Temple, Listen! All of you: The word of Psol remains alive and vibrant throughout the ages; it neither needs no special interpretation, nor holds any hidden secrets. It is absolute in its teaching, and cuts every Kinne to the heart in matters of the soul. Never will you need more than these scriptures in life. If anyone will preach to you using bombastic speech to pull away your brethren for profit, speak of a different, secret revelation, or claims there is more to the divine than the inspired texts, do not allow him into your chapels; do not allow such Kinne to perform in your Temple, until such a teaching has been weighed against the Codex with prayer and fasting. For there are many Kinne who would work the teachings of mysticism, sorceries, and blood sacrifice of the Wild Ones, and other strange practices into our faith.

Latter Annals, chapter 30

“NO, no,” Alyss said, holding up her paw. “That,” she said with some difficulty, “will be enough.”

“Ye only had two,” Baslev said, pouring himself yet another glass.

“Why, why do you drink this?” she asked, as the barmaid brought them food. Alyss poked at her cheese and nut-paste sandwich idly.

Baslev watched her, crunching a carrot. “Why d’ye pray to Psol?”

Alyss leaned back and squinted at Baslev, grimacing in confused disbelief.

Baslev waited for a response, finishing his carrot, maintaining eye contact with Alyss as he brushed his paws off on themselves, and then grabbed the next thing on his plate without looking, which happened to be a large stalk of celery. Crunch.

“What does that have to do with tato?”

“Everythin’.”

Alyss felt even more confused, and her whiskers twitched. Baslev downed the shot and slammed the glass on the table.

“I drink, y’see, I drink,” Baslev said, pouring another, “te make the bad things less bad, and the good things better.”

Alyss held up her paws, grimacing more deeply in disbelief. “That…has nothing to do with it.”

“Och, an’ I suppose ye pray te make things worse?” Crunch. “Ye pray te Psol, ye does, listen the noo, think about it, te make the bad things less bad, right? And the good things better.”

“It’s not as simple as that, Psol is real, and alive, and listens, and actually makes things happen. This… this tato—“

“Tato,” he corrected her, pronouncing it the other way.

“Tato, tato, it makes no difference,” Alyss said, waving her paws about in frustration, “cannot answer me when I cry out. It cannot act upon the heavens and influence planetary events. It did not stitch me together according to my parts. It does not think, it does not feel, it does nothing,” she said, taking a deep breath, “but help you escape your problems.”

Baslev cleared his throat, licked his lips, then tapped his head with the celery. “Och, like I caught ye doin’, runnin’ down the lane, all desperate-like?”

Alyss blinked. She did not know what to say.

Crunch.

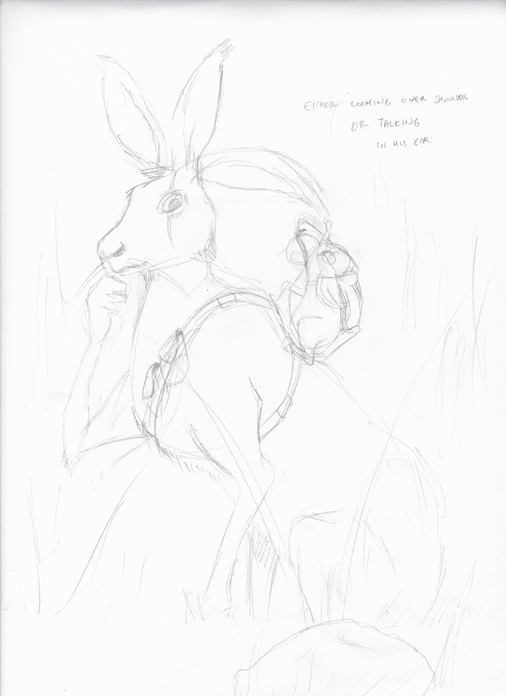

Alyss huffed and took a bite of her sandwich. She mulled the conversation over in her head as she mulled the bite about in her mouth, leaning back in her pouf. “What about you, my good hare? It is as if you have no care for Psol, or His plan for you.”

“Well tha’s just it, innit?” he replied, pointing at her with the stump of his celery. “Lots o’Kinne don’t really care, they don’t.”

“I am afraid I do not,” Alyss said, suppressing a burp, “have any idea what you are talking about.”

“See, ye live in yer high castle, ye clerical types do,” Baslev said, picking up another stalk of celery and pausing to crunch. “Ye don’t see the real world, ye don’t. Out here, things are hard, and we get on just fine without yer fairy stories te tell us what we can and can’t do.”

Alyss was taken aback. “Baslev, we were drawn out of the Wild Ones and created as the Kinne for great works. Damoss gave us the Law so that we could better live in harmony with—”

“No, no, no,” Baslev interrupted with his mouth full, “because it’s all so complicated, see? Ye priests, ye have all yer pomp, an’ yer circumstance, but the Codex says one thing, and ye do another. Well maybe not you, Miss Alyss,” Baslev added with a wink.

Alyss’s chest burned with the compliment, for Baslev only saw what she put on the outside. “Very well,” she sighed, “pour me another, then.”

“Righto.”

Alyss drank and gagged again, making a different array of faces than before.

“The first one,” Baslev said, reaching for a skein of clover, “is te numb yer tongue fer the second one.” He grinned.

“Gnuaaugh, and what of the third?”

“Fer correctin’ the discrepancies that the second may, or may not, have overlooked.” He said this sentence with a rather fancy air about him, a digit in the air, and looked quite proud of himself.

They ate in relative silence for a while. Then, after making it halfway through her sandwich, Alyss set it down, finished her third drink, and volunteered, “I want to get out of Delta.”

Baslev nodded.

“I can’t stay here,” Alyss said, looking at the bottom of her glass, holding it with both paws. She held her paw over top of it when Baslev picked up the bottle.

“Well,” Baslev said with a shrug, swirling what was left of the bottle about over his head and peering through it with one eye, “I’m leavin’ tomorrow, I am. I could take ye to the monastery on me way out.”

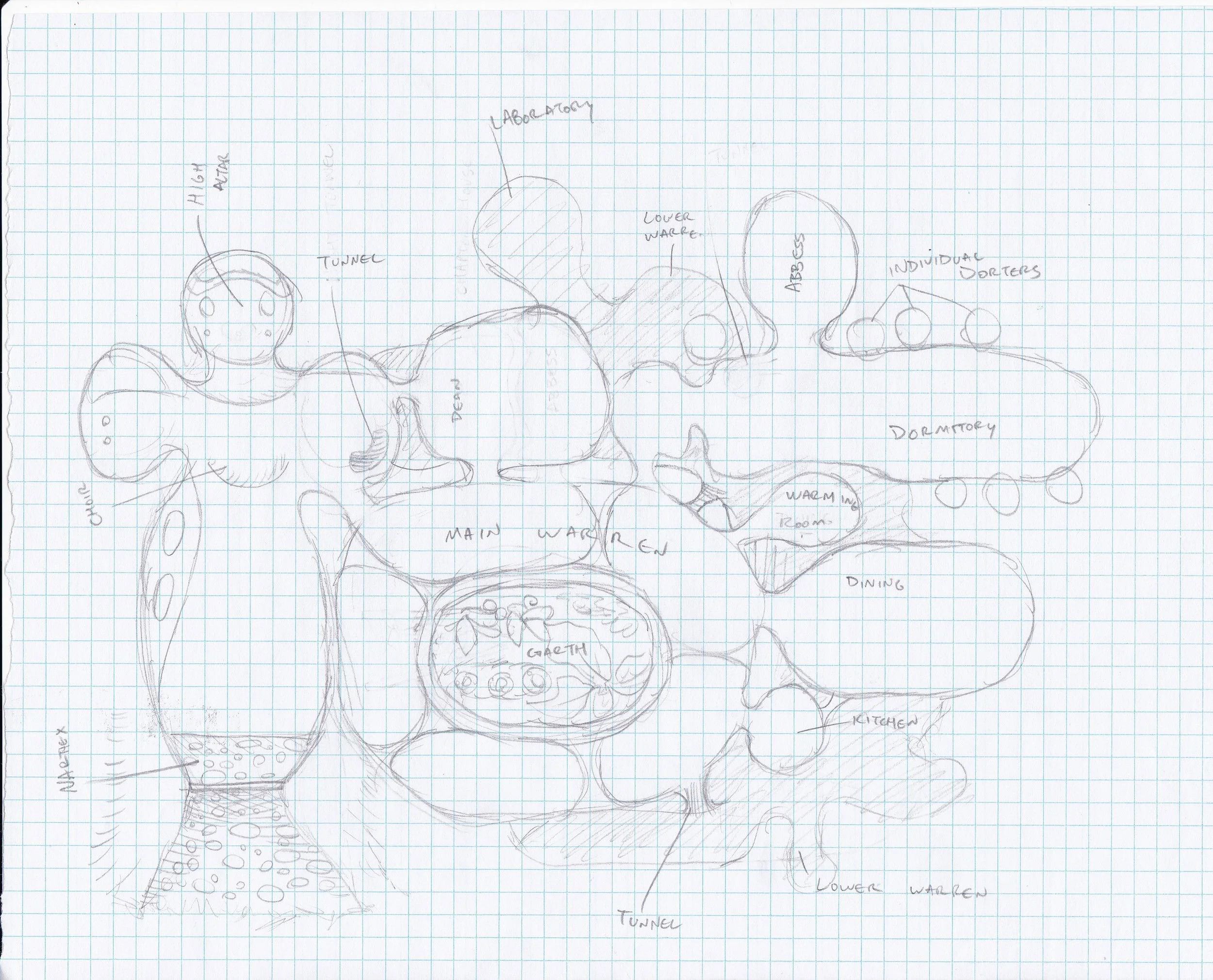

“No, I can’t stay there, either,” Alyss sighed. She knew that anywhere where there were clerical duties to be filled, there was someone who would gladly help the Prime Hierarch. Who wouldn’t? He led the city-state of Delta as figurehead and emissary to Psol. She rubbed her head, which felt heavy, like a large stone attached to a leather strap, continuing to attempt rolling away, but just lolling about instead.

“Well,” Baslev said again, finishing his grass, “I’m leavin’ tomorrow.”

“Yes, you said that. Where are you going?”

“Does it matter, Miss?”

“I should suspect that it rather does,” Alyss said, raising a brow.

“Ringwell.”

“Ringwell?”

“Ringwell?” he squawked. “Aye, the same.”

“Isn’t that rather far away?”

“Probably not,” Baslev said with a shrug. “Been farther.”

Alyss took another bite of her sandwich. It was a particularly good sandwich. The cheese they used was especially pungent, and went well with the meaty flavor of the nut-paste. “I don’t know, Baslev.”

“Suddenly got cold feet, ‘ave ye then? Do ye no like adventure?”

“I should say I don’t.”

“Do ye no like te go fast, and feel the wind in yer fur, the sun in yer eyes, foragin’ fer food, sleepin’ under a dark canopy o’trees?”

“I am most certain I like the opposite of these things,” Alyss said, “I like the indoors, a warm hearth, a roof over my head, and sleeping in the same bed every night.”

Baslev scoffed. He made sputtering noises. He looked in all directions and scoffed again a few times, for good measure. “Mice.” He picked up his coin purse.

Alyss reached forward to grab her own purse to pay for her sandwich, but Baslev frowned and shook his head. Alyss shrugged; it was her brother’s money, anyway, and all she had. He’d insisted on paying her for helping in the shop.

He pulled out five silver rumards and placed them on the table with a wink at Alyss. He picked up what was left of her cheese and nut-paste sandwich and gave it a sniff. His nose turned up and he tossed the sandwich back. “Cheese,” he coughed. “Expensive doe, ye are.”

Tucking the bottle under his arm, Baslev stood and offered his paw to Alyss. She tittered and took his paw, and he helped her off of her pouf. She was glad for it, for she found that neither the pouf nor the floor were quite agreeing with her. It was wobbling about in a most unruly manner. She reminded herself to scold it later.

Alyss rode on Baslev’s shoulders back to the coffee shop. She saw that the sun had already gone down. She hadn’t realized so much time had passed over three drinks and one sandwich. He helped her down and gave her the bottle of tato.

“No,” she said sleepily, “You take it, I don’t want it.”

“I’ll see ye on the morrow, then.”

“What? No, I won’t be going with you,” she said, taking the bottle.

“Righto. Tomorrow then.”

Alyss groaned and leaned against the door to Trespasser’s Drop, then slipped in, bottle tucked under her arm. Eleander was cleaning up; her father was sitting by the kettle, keeping warm.

“I am going to bed,” she announced, feeling rather proud of herself.

“Bed? You just got here; where have you been all day?” Eleander asked, tilting his head and raising a brow. “The way you left, I had genuine cause for concern.”

“I thought you had been eaten,” her father offered.

“How delightfully morbid, Daddy.” She smiled sleepily. “I had dinner with a friend, and now I am off to bed. Apparently tomorrow, I am to go on an adventure.”

“Take your brother, he needs the fresh air,” her father called down after her, wheezing and hacking near the end.

Again, as with the dwale, Alyss found that after having drunk the tato with Baslev, and then dizzily slid into her cot, she had naught but a strange, vague dream. She awoke suddenly the next morning to a puddle of drool on her pillow. The dream had been about Qireth, and while she did not recall it as particularly nightmarish, she catalogued it as a nightmare anyway, just to be safe.

“You have a visitor,” said her brother, peeking in at the door. “Are you truly leaving? We must talk about yesterday.”

Alyss groaned as she shook her head. Her head felt as if it was filled with some sort of vile, gelatinous cheese, and her mouth felt as if it was stuffed with paper. She sat up and wiped the drool off of the left side of her face with a grimace, and squinted at Eleander, who pursed his lips and backed slowly out of the guest room.

She sat on the edge of the bed, considered praying, and could not decide if she wanted to or not. She also could not decide if she wanted to ever drink tato again, even if it meant a decent night’s sleep. Another thought entered her mind: what if Psol was unhappy with the reckless approach she was beginning to consistently take towards sleep and dreaming, and the way it was beginning to make her neglect her times she usually set aside for worship and reading scripture? Clucking her tongue, which stuck awkwardly to the roof of her mouth, she pushed that thought out of her mind, deciding to deal with it later, and instead poured herself a glass from the bedside pitcher.

She could not decide if drinking water made it worse, or better, either.